Can't find what you're looking for here? We can help!

Contact usCan't find what you're looking for here? We can help!

Contact us“I’m such a luddite.” is a phrase that I sometimes hear when helping someone with a technology problem. “Luddite” in this case is a self-deprecating term referring to someone who doesn’t like or isn’t good with new technology. However, the term Luddite has far more interesting origins that are still relevant today.

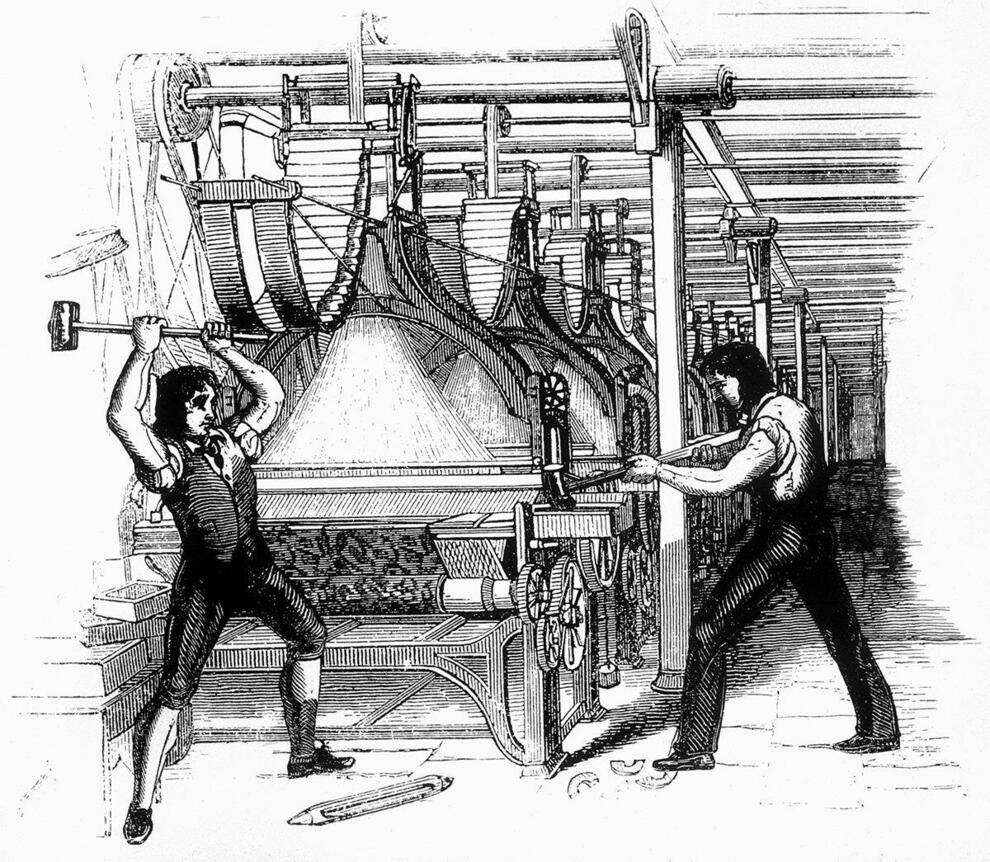

1812 etching depicting luddites

"frame breaking"

The Luddites were members of a labour movement during the early years of the Industrial Revolution. Far from being anti-technology, members of the movement were concerned with textile mill owners using automated machinery to avoid hiring skilled, properly trained workers at a fair wage. They protested this by selectively smashing the knitting machines of mill owners that engaged in this practice.

The Luddites weren’t the first or only group to engage in this kind of protest. The Swing Riots in the 1830’s saw a similar rage against the machine as farm workers battling against low wages and poor working conditions took aim at threshing machines which had reduced the number of jobs. Again, it wasn’t the technology itself that was at issue, but technology being used in a way that failed to make life better for people.

Even though the Luddites and similar movements are remembered today, erroneously, for their anti-technology stance, their aim wasn’t to eliminate technology and go back to older ways of doing things. Rather they wanted to be sure that the use of technology wasn’t eroding the way of life that was helping them put food on the table. These movements, while tumultuous, ultimately resulted in improved conditions for workers at the time.

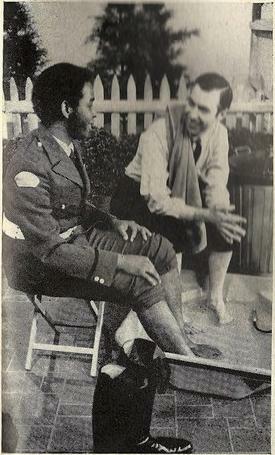

Mr. Rogers sharing a foot bath with

François Clemmons in 1969

Another person you might not think of having a critical impact on technology is Fred Rogers – as in Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, Fred Rogers. In the mid-1950s, Mr. Rogers was experimenting with a relatively new technology at the time – television. He was very concerned about the content that children were seeing on television, and the overall quality of what little children’s programming was being produced. His approach was to use this technology in an intentional way, using principles of childhood development, to create television programming that would nurture and enrich young children.

Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood’s focus was on empathy and helping children navigate their feelings, whether in response to normal everyday things like play, sibling rivalry, and conflict with parents, or more serious things like frightening global events. One of Mr. Rogers’ legacies was in his successful address to the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Communications in 1969 that helped retain funding for the newly formed Corporation for Public Broadcasting in the United States. The intentional use of technology to support child development is also an ongoing position of the Fred Rogers Institute whose focus is on the healthy development of children.

Mr. Rogers looked at the technology of his time with a specific goal in mind, and carefully crafted a solution using that technology to solve a problem he saw, and experienced, in the life of the American child. When he saw technology potentially causing harm, he used what power he had to create a public good instead. In his words (as recounted by journalist Jeff Greenfield) "I got into television because I hated it so, and I thought ... there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to be of nurture to those who would watch and listen."

Today, how technology impacts the wellbeing of society continues to challenge us. Right now, the Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) and the Writers Guild of America (WGA) are on strike in part because technology has contributed to a decline in working conditions in the Film and Television industry. Two of these issues are streaming services and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Both of these technological changes are very new, and they emerged before their impact on labour conditions could be negotiated by the workers impacted by them the most. In the case of streaming, studios have been using this more and more as audience demand rose for the ability to watch a show or movie anytime, anywhere. However, streaming doesn’t have the same rules bargained for in terms of compensation – so moving to streaming at the expense of film and television has allowed studios to pay performers less for the same amount of work.

WGA East writers picketing

(Photo: Natalia Marques)

Source: Peoples Dispatch

CC BY-SA 4.0

AI might be the topic of a whole article by itself someday, but specific to the SAG-AFTRA strike is how a performers likeness can be captured, animated using AI technology, and then used in perpetuity without the consent of the performer, and without later compensation for additional work using that likeness. Similar questions about AI and usage rights are emerging around authors whose works have been pirated online, and then scraped by AI companies to train programs such as ChatGPT, and visual artists who have posted samples of their work online to market their art only to find they have been used to train AI image generators like DALL-E which in turn create content that is derived from that work and can be used to devalue that work.

Like the Luddite movement before them, creative professions are seeing an erosion of their livelihood by technology that could ultimately affect, and in some ways is already affecting, the wider population. They are the canaries in this coal mine. And we are, in a lot of ways, having our Mr. Rogers moment when it comes to the newest technology of our day. While it is true that automation and technology can displace jobs and contribute to inequity (according to MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, this has been a driving factor of the income gap since the 1980’s), there is an honest discussion to be had about how these very same technologies can enrich our lives if we use them with the public good in mind. But to do that, we have to understand how to avoid using technology to undermine the wellbeing of others, and we need to build new systems that allow us to thrive even as our world changes.

By Erin Kernohan-Berning